The qawwali, a duet or baitbazi (poetic contest) between Madhubala’s Anarkali (Lata Mangeshkar) and Nigar Sultana’s conniving Bahar (Shamshad Begum), is disconcertingly prescient and holds several clues to Mughal-E-Azam’s evolving and unfolding narrative. It’s a David-Goliath of the worst kind.Īs popular as “Pyaar kiya toh darna kya” is, one song that turns out to be the most central to the film’s narrative is “Teri mehfil mein qismat”. More importantly, she’s up against the much-feared emperor himself. “Mohabbat ki jhoothi kahani pe roye”, another Mughal-E-Azam gem featuring Madhubala, expresses an imprisoned Anarkali’s helplessness and uncertain future while Rafi’s “Aye mohabbat zindabad” is a protest anthem that flies in the face of emperor Akbar’s objection to son Salim’s romance with Anarkali. With her open defiance of Akbar, her irreverence to authority and declaration of love for the princeling, Anarkali challenges the Mughal court and the iconic “Pyaar kiya toh darna kya” testifies to her courage and pure love. As the rebel Anarkali humbles the might of emperor Akbar, perhaps the most powerful man in India of the time, her reflection giving further depth to Shakeel Badayuni’s powerful lines (‘Chhup na sakega ishq hamara/ Charo taraf hai unka nazara’), the song is a Mughal-level mausoleum to Madhubala’s memory and is still associated with the Golden Era enchantress. The only ‘colour’ song in an otherwise B&W film, it was shot at the exquisite Sheesh Mahal, a replica of the Lahore Fort built on a set at Mohan Studio, Bombay. More than five decades on, it reminds you that there cannot be a better metaphor for the Anarkali legend.

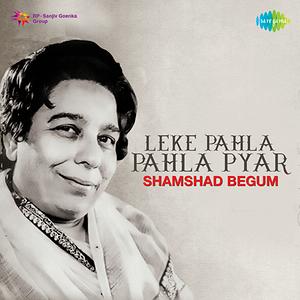

However, going purely by the audience choice, “Pyaar kiya toh darna kya” remains the film’s best-loved song. “Prem jogan ban ke” in raga Sohini captures the heady romance between Anarkali and Salim while the raga Rageshree-inspired “Shubh din aayo” hums in the background as the prodigal son returns, instantly spreading cheer and happiness in the Mughal kingdom. Their collaboration resulted in two songs, both sung by Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Apparently, just to get rid of the single-mindedly obsessed filmmaker, Khan had demanded an absurdly astronomical fee for the assignment (no less than Rs 25,000 at a time when Rafi and Lata’s price was about Rs 400 per song). It is rumoured that the maestro had, at first, declined the Mughal-E-Azam offer because those days (perhaps, as true today as then) classical doyens looked down upon films. Not to mention the small but significant contribution from Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. There’s Naushad as composer, Shakeel Badayuni on lyrics and Lata Mangeshkar, Mohammed Rafi and Shamshad Begum on playback. If the screen line-up of Prithviraj Kapoor (as the upstanding and just emperor Akbar), Madhubala, Dilip Kumar, Durga Khote and Ajit gives you goosebumps wait till you hear the legends fronting the music credits. Diehard fans agree that it’s a near-perfect film, but so is Naushad’s score and the soundtrack which is equally flawless and divine, an album of Mozartian power and scale. Undoubtedly, music has also helped its legacy in a significant way. Based on a 1920s play by Urdu dramatist Imtiaz Ali Taj, Mughal-E-Azam’s greatest legacy lies in its dramatic plot, poetic dialogue, memorable acting and grand vision of its makers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)